- Home

- Linda Nagata

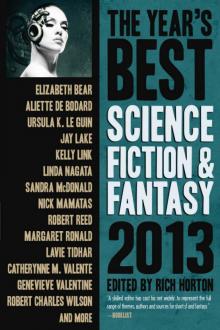

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013 Page 2

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013 Read online

Page 2

“Magistrate, this is a minor case—”

“There are no minor cases, Officer Choy. You’re dismissed for now, but please, wait outside.”

There was nothing else I could do. I left the room knowing Key Lu was a dead man.

I could have cleaned things up if I’d just had more time. I could have cured Key Lu. I’m a molecular designer and my skills are the reason I was drafted into the Commonwealth police.

Technically, I could have refused to join, but then my home city of Haskins would have been assessed a huge fine—and the city council would have tried to pass the debt on to me. So I consoled myself with the knowledge that I would be working on the cutting edge of molecular research and, swallowing my misgivings, I swore to uphold the laws of the Commonwealth, however arcane and asinine they might be.

I worked hard at my job. I tried to do some good, and though I skirted the boundaries now and then, I made very sure I never went too far because if I got myself fired, the debt for my training would be on me, and the contracts I’d have to take to pay that off didn’t bear thinking on.

The magistrate required me to attend the execution, assigning me to stand watch beside the door. I used a mood patch to ensure a proper state of detachment. It’s a technique they taught us at the academy, and as I watched the two other officers escort Key Lu into the room, I could tell from their faces they were tranked too, while Key Lu was glassy-eyed, more heavily sedated than the rest of us.

He was guided to a cushioned chair. One of the cops worked an IV into his arm. Five civilians were present, seated in a half circle on either side of the magistrate. One of them was weeping. Her name was Hera Poliu. I knew her because she was a friend of my intimate, Tishembra Indens—but Tishembra had never mentioned that Hera and Key were involved.

The magistrate spoke, summarizing the crime and the sanctity of Commonwealth law, reminding us the law existed to guard society’s shared idea of what it means to be human, and that the consequences of violating the law were mandated to be both swift and certain. She nodded at one of the cops, who turned a knob on the IV line, admitting an additional ingredient to the feed. Key Lu slumped and closed his eyes. Hera wept louder, but it was already over.

Nahiku was justly famed for its vista walls, which transformed blank corridors into fantasy spaces. On Level Seven West, where I lived, the theme was a wilderness maze, enhanced by faint rainforest scents, rustling leaves, bird song, and ghostly puffs of humidity. Apartment doors didn’t appear until you asked for them.

The path forked. I went right. Behind me, a woman called my name, “Officer Choy!” Her voice was loud and so vindictive that when the DI whispered in my mind, Hera Poliu, I thought, No way. I knew Hera and she didn’t sound like that. I turned fast.

It was Hera all right, but not like I’d ever seen her. Her fists were clenched, her face flushed, her brows knit in a furious scowl. The DI assessed her as rationally angry, but it didn’t seem that way to me. When she stepped into my personal space I felt a chill. “I want to file a complaint,” she informed me.

Hera was a full head shorter than me, thin and willowy, with rich brown skin and auburn hair wound up in a knot behind her head. Tishembra had invited her over for dinner a few times and we’d all gone drinking together, but as our eyes locked I felt I was looking at a stranger. “What sort of complaint, Hera?”

“Don’t patronize me.” I saw no sign in her face of the heart-rending grief she’d displayed at the execution. “The Commonwealth police are supposed to protect us from quirks like Key.”

“Key never hurt anyone,” I said softly.

“He has now! You didn’t hear the magistrate’s assessment. She’s fined the city for every day since Key became a citizen. We can’t afford it, Choy. You know Nahiku already has debt problems—”

“I can’t help you, Hera. You need to file an appeal with the magistrate—”

“I want to file a complaint! The city can’t get fined for harboring quirks if we turn them in. So I’m reporting Tishembra Indens.”

I stepped back. A cold sweat broke out across my skin as I looked away.

Hera laughed. “You already know she’s a quirk, don’t you? You’re a cop, Choy! A Commonwealth cop, infatuated with a quirk.”

I lost my temper. “What’s wrong with you? Tishembra’s your friend.”

“So was Key. And both of them immigrants.”

“I can’t randomly scan people because they’re immigrants.”

“If you don’t scan her, I’ll go to the magistrate.”

I tried to see through her anger, but the Hera I knew wasn’t there. “No need to bother the magistrate,” I said softly, soothingly. “I’ll do it.”

She nodded, the corner of her lip lifting a little. “I look forward to hearing the result.”

I stepped into the apartment to find Tishembra’s three-year-old son Robin playing on the floor, shaping bridges and wheels out of colorful gel pods. He looked up at me, a handsome boy with his mother’s dark skin and her black, glossy curls, but not her reserved manner. I was treated to a mischievous grin and a firm order to, “Watch this!” Then he hurled himself onto his creations, smashing them all back into disks of jelly.

Tishembra stepped out of the bedroom, lean and dark and elegant, her long hair hanging down her back in a lovely chaos of curls. She’d changed from her work clothes into a silky white shift that I knew was only mindless fabric and still somehow it clung in all the right places as if a DI was controlling the fibers. She was a city engineer. Two years ago she’d emigrated to Nahiku, buying citizenship for herself and Robin—right before the city went into massive debt over an investment in a water-bearing asteroid that turned out to have no water. She was bitter over it, more so because the deal had been made before she arrived, but she shared in the loss anyway.

I crossed the room. She met me halfway. I’d been introduced to her on my second day at Nahiku, seven months ago now, and I’d never looked back. Taking her in my arms, I held her close, letting her presence fill me up as it always did. I breathed in her frustration and her fury and for a giddy moment everything else was blotted from my mind. I was addicted to her moods, all of them. Joy and anger were just different aspects of the same enthralling, intoxicating woman—and the more time I spent with her the more deeply she could touch me in that way. It wasn’t love alone. Over time I’d come to realize she had a subtle quirk that let her emotions seep out onto the air around her. Tishembra tended to be reserved and distant. I think the quirk helped her connect with people she casually knew, letting her be perceived as more open and likeable, and easing her way as an immigrant into Nahiku’s tightly-knit culture—but it wasn’t something we could ever talk about.

“You were part of it, weren’t you?” she asked me in an angry whisper. “You were part of what happened to Key. Why didn’t you stop it?”

Tishembra had taken a terrible chance in getting close to me.

Her fingers dug into my back. “I’m trapped here, Zeke. With the new fine, on top of the old debt . . . Robin and I will be working a hundred years to earn our way free.” She looked up at me, her lip curled in a way that reminded me too much of Hera’s parting expression. “It’s gotten to the point, my best hope is another disaster. If the city is sold off, I could at least start fresh—”

“Tish, that doesn’t matter now.” I spoke very softly, hoping Robin wouldn’t overhear. “I’ve received a complaint against you.”

Her sudden fear was a radiant thing, washing over me, making me want to hold her even closer, comfort her, keep her forever safe.

“It’s ridiculous, of course,” I murmured. “To think you’re a quirk. I mean, you’ve been through the gates. So you’re clean.”

Thankfully, my DI never bothered to point out when I was lying.

Tishembra nodded to let me know she understood. She wouldn’t tell me anything I didn’t want to know; I wouldn’t ask her questions—because the less I knew, the better.

My hope

rested on the fact that she could not have had the quirk when she came through the port gate into Nahiku. Maybe she’d acquired it in the two years since, or maybe she’d stripped it out when she’d passed through the gate. I was hoping she knew how to strip it again.

“I have to do the scan,” I warned her. “Soon. If I don’t, the magistrate will send someone who will.”

“Tonight?” she asked in a voice devoid of expression. “Or tomorrow?”

I kissed her forehead. “Tomorrow, love. That’s soon enough.”

Robin was asleep. Tishembra lay beside him on the bed, her eyes half closed, her focus inward as she used her atrium to track the progress of processes I couldn’t see. I sat in a chair and watched her. I didn’t have to ask if the extraction was working. I knew it was. Her presence was draining away, becoming fainter, weaker, like a memory fading into time.

After a while it got to be too much, waiting for the woman I knew to become someone else altogether. “I’m going out for a while,” I said. She didn’t answer. Maybe she didn’t hear me. I re-armed myself with my chemical arsenal of gel ribbons. Then I put my uniform back on, and I left.

All celestial cities have their own municipal police force. It’s often a part-time, amateur operation, but the local force is supposed to investigate traditional crimes like theft, assault, murder—all the heinous things people have done to each other since the beginning of time. The Commonwealth police are involved only when the crime violates statutes involving molecular science, biology, or machine intelligence.

So strictly speaking, I didn’t have any legal right or requirement to investigate the original accident that had exposed Key’s quirk, but I took the elevator up to Level 1 West anyway, and used my authority to get past the DI that secured the railcar garage.

Nahiku is a twin orbital. Its two inhabited towers are counterweights at opposite ends of a very long carbon-fiber tether that lets them spin around a center point, generating a pseudogravity in the towers. A rail runs the length of the tether, linking Nahiku East and West. The railcar Key Lu had failed to die in was parked in a small repair bay in the West-end garage. Repair work hadn’t started on it yet, and the two small holes in its canopy were easy to see.

There was no one around, maybe because it was local-night. That worked for me: I didn’t have to concoct a story on why I’d made this my investigation. I started collecting images, measurements, and sample swabs. When the DI picked up traces of explosive residue, I wasn’t surprised.

I was inside the car, collecting additional samples from every interior surface, when a faint shift in air pressure warned me a door had opened. Footsteps approached. I don’t know who I was expecting. Hera, maybe. Or Tishembra. Not the magistrate.

Glory Mina walked up to the car and, resting her hand on the roof, she bent down to peer at me where I sat on the ruptured upholstery.

“Is there more going on here that I need to know about?” she asked.

I sent her the DI’s report. She received it in her atrium, scanned it, and followed my gaze to one of the holes in the canopy. “You’re thinking someone tried to kill him.”

“Why like this?” I wondered. “Is it coincidence? Or did they know about his quirk?”

“What difference does it make?”

“If the attacker knew about Key, then it was murder by cop.”

“And if not, it was just an attempted murder. Either way, it’s not your case. This one belongs to the city cops.”

I shook my head. I couldn’t leave it alone. Maybe that’s why my superiors tolerated me. “I like to know what’s going on in my city, and the big question I have is why? I’m not buying a coincidence. Whoever blew the canopy had to know about Key—so why not just kill him outright? If he’d died like any normal person, I wouldn’t have looked into it, you wouldn’t have assessed a fine. Who gains, when everyone loses?”

Even as I said the words my thoughts turned to Tishembra, and what she’d said. It’s gotten to the point, my best hope is another disaster. No. I wasn’t going to go there. Not with Tishembra. But maybe she wasn’t the only one thinking that way?

The magistrate watched me closely, no doubt recording every nuance of my expression. She said, “I saw the complaint against your intimate.”

“It’s baseless.”

“But you’ll look into it?”

“I’ve scheduled a scan.”

Glory nodded. “See to that, but stay out of the local case. This one doesn’t belong to you.”

The apartment felt empty when I returned. I panicked for the few seconds it took me to sprint across the front room to the bedroom door. Tishembra was still lying on the bed, her half-closed eyes blinking sporadically, but I couldn’t feel her. Not like before. A sense of abandonment came over me. I knew it was ridiculous, but I felt like she’d walked away.

Robin whimpered in his sleep, turned over, and then awoke. He looked first at Tishembra lying next to him, and then he looked at me. “What happened to mommy?”

“Mommy’s okay.”

“She’s not. She’s wrong.”

I went over and picked him up. “Hush. Don’t ever say that to anyone but me, okay? We need it to be a secret.”

He pouted, but he was frightened, and he agreed.

I spent that night in the front room, with Robin cradled in my arm. I didn’t sleep much. I couldn’t stop thinking about Key and his quirk, and who might have known about it. Maybe someone from his past? Or someone who’d done a legal mod on him? I had the DI import his personal history into my atrium, but there was no record of any bioengineering work being done on him. Maybe it had just been a lucky guess by someone who knew what went on in the Far Reaches? I sent the DI to search the city files for anyone else who’d ever worked out there. Only one name came back to me: Tishembra Indens.

Tishembra and I had never talked much about where we’d come from. I knew circumstances had not been kind to her, but that she’d had to take a contract in the Far Reaches—that shocked me.

My best hope is another disaster.

I deleted the query, I tried to stop thinking, but I couldn’t help reflecting that she was an engineer. She had skills. She could work out how to pop the canopy and she’d have access to the supplies to do it.

Eventually I dozed, until Tishembra woke me. I stared at her. I knew her face, but I didn’t know her. I couldn’t feel her anymore. Her quirk was gone, and she was a stranger to me. I sat up. Robin was still asleep and I cradled his little body against my chest, dreading what would happen when he woke.

“I’m ready,” Tishembra said.

I looked away. “I know.”

Robin wouldn’t let his mother touch him. “You’re not you!” he screamed at her with all the fury a three-year-old could muster. Tishembra started to argue with him, but I shook my head, “Deal with it later,” and took him into the dining nook, where I got him breakfast and reminded him of our secret.

“I want mommy,” he countered with a stubborn pout.

I considered tranking him, but the staff at the day-venture center would notice and they would ask questions, so I did my best to persuade him that mommy was mommy. He remained skeptical. As we left the apartment, he refused to hold Tishembra’s hand but ran ahead instead, hiding behind the jungle foliage until we caught up, then running off again. I didn’t blame him. In my rotten heart I didn’t want to touch her either, but I wasn’t three. So the next time he took off, I slipped my arm around Tishembra’s waist and hauled her aside into a nook along the path. We didn’t ever kiss or hold hands when I was in uniform and besides, I’d surprised her when her mind was fixed on more serious things, so of course she protested. “Zeke, what are you doing?”

“Hush,” I said loudly. “Do you want Robin to find us?”

And I kissed her. I didn’t want to. She knew it, and resisted, whispering, “You don’t need to feel sorry for me.”

But I’d gotten a taste of her mouth, and that hadn’t changed. I wanted more. She felt it and sof

tened against me, returning my kiss in a way that made me think we needed to go back to the apartment for a time.

Then Robin was pushing against my hip. “No! Stop that kissing stuff. We have to go to day-venture.”

I scowled down at him. “Fine, but I’m holding Tishembra’s hand.”

“No. I am.” And to circumvent further argument, he seized her hand and tugged her toward the path. I let her go with a smirk, but her defiant gaze put an end to that.

“I do love you,” I insisted. She shrugged and went with Robin, too proud to believe in me just yet.

Day-venture was on Level 5, where there was a prairie vista. On either side of the path we looked out across a vast land of low, grassy hills, where some sort of herd animals fed in the distance. Waist-high grass grew in a nook outside the doorway to the day-venture center. Robin stomped through it, sending a flutter of butterflies spiraling toward a blue sky. The grass sprang back without damage, betraying a biomechanical nature that the butterflies shared. One of them floated back down to land on Tishembra’s hand. She started to shoo it away, but Robin shrieked, “Don’t flick it!” and he pounced. “It’s a message fly.” The butterfly’s blue wings spread open as it rested in his small palms. A message was written there, shaped out of white scales drained of pigment, but Robin didn’t know how to read yet, so he looked to his mother for help. “What does it say?”

Tishembra gave me a dark look. Then she crouched to read the message and I saw a slight uptick in the corner of her lip. “It says Robin and Zeke love Tishembra.” Then she ran her finger down the butterfly’s back to erase the message, and nudged it, sending it fluttering away.

“It’s wrong,” Robin told her defiantly. “I don’t love Tishembra. I love mommy.” Then he threw his arms around her neck and kissed her, before running inside to play with his friends.

Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories

Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories Pacific Storm

Pacific Storm Edges

Edges The Red

The Red The Red: First Light

The Red: First Light The Martian Obelisk

The Martian Obelisk Limit of Vision

Limit of Vision Going Dark

Going Dark The Last Good Man

The Last Good Man The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2)

The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2) Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2)

Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2) The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013 The Dread Hammer

The Dread Hammer Skye Object 3270a

Skye Object 3270a The Bohr Maker

The Bohr Maker