- Home

- Linda Nagata

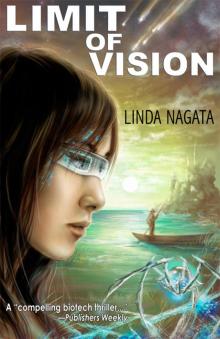

Limit of Vision

Limit of Vision Read online

Limit of Vision

Linda Nagata

Published by Mythic Island Press LLC

Kula, Hawaii

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are fictitious or are used fictitiously.

Limit of Vision

Copyright © 2001 by Linda Nagata.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

This novel was first published by Tor®/Tom Doherty Associates, LLC in March 2001.

Mythic Island Press LLC electronic edition January 2011.

ISBN 978-0-9831100-6-4

Cover Art Copyright © 2011 Mythic Island Press LLC

Cover Concept by Linda Nagata

Digital Painting by Sarah Adams – www.mythicislandpress.com/SarahAdams

Mythic Island Press LLC

PO Box 1293

Kula, HI 96790-1293

MythicIslandPress.com

This copy of Limit of Vision was purchased from Book View Café

Acknowledgments From the Original Edition

Limit of Vision was a long time in the making, and many people helped along the way. Thanks are due to Mark O. Martin, who suggested Agrobacterium tumefaciens, blue-green light, and other delectables. To Howard Morhaim, for putting up with me when I dumped the original manuscript and started over. To Sean Stewart, Kathleen Ann Goonan, and Wil McCarthy, for reading the story-in-progress and offering invaluable suggestions. To Thuy Da Lam, for providing Vietnamese phrases and vetting the manuscript for cultural flaws. (Any remaining errors are my own.) And to my husband, Ron, whose confidence in me always far exceeds my own.

chapter

1

THE AGE HAD its own momentum. Virgil Copeland could sense it. Even here, now, as he waited anxiously for Gabrielle it tugged at him, whispering there was no going back.

He stood watch by the glass doors of the Waimanalo retreat center, willing Gabrielle’s car to appear at the end of the circular driveway. He imagined it gliding into sight around the bank of lush tropical foliage—heliconia and gardenias, ornamental ginger and potted orchids—their flowers bright in the muted light beneath heavy gray clouds.

But Gabrielle’s car did not appear. She didn’t call. All afternoon she had failed to respond to Virgil’s increasingly frantic messages. He couldn’t understand it. She had never been out of contact before.

Randall Panwar stopped his restless pacing, to join Virgil in his watch. “She should have been here hours ago. Something’s happened to her. It has to be.”

Virgil didn’t want to admit it. He touched his forehead, letting his fingertips slide across the tiny silicon shells of his implanted LOVs. They felt like glassy flecks of sand: hard and smooth and utterly illegal.

“Don’t do that,” Panwar said softly. “Don’t call attention to them.”

Virgil froze. Then he lowered his hand, forcing himself to breathe deeply, evenly. He had to keep control. With the LOVs enhancing his moods, it would be easy to slide into an irrational panic. Panwar was susceptible too. “You’re doing all right, aren’t you?” Virgil asked.

Panwar looked at him sharply, his eyes framed by the single narrow wraparound lens of his farsights. Points of data glinted on the interactive screen.

Panwar had always been more volatile than either Virgil or Gabrielle, and yet he handled his LOVs best. The cascading mood swings that Virgil feared rarely troubled him. “I’m worried,” Panwar said. “But I’m not gone. You?”

“I’ll let you know.”

Panwar nodded. “I’ve got sedatives, if you need them.”

“I don’t.”

“I’ll try to message her again.”

He bowed his head, raising his hand to touch his farsights, as if he had to shade out the external world to see the display. He’d had the same odd mannerism since Virgil had met him—eight years ago now—when they’d been assigned to share a frosh dorm room, shoved together because they’d both graduated from technical high schools, and because they were both sixteen.

Panwar’s dark brown hair displayed a ruddy Irish tinge, courtesy of his mother. By contrast his luminous black eyes were a pure gift of his father: Ancient India in a glance. At six-three he was several inches taller than Virgil, with the lean, half-wasted build of a starving student out of some nineteenth-century Russian novel. Not that he had ever wanted for money—his parents were both computer barons, and all that he had ever lacked was time. Then again, it would take an infinite amount of time to satisfy his curiosities.

He looked up. A short, sharp shake of his head conveyed his lack of success. “Let’s drive by her place when we get out of here.” His own implanted LOVs glittered like tiny blue-green diamonds, scattered across his forehead, just beneath his hairline. Like Gabrielle, he passed them off as a subtle touch of fashionable glitter.

Virgil’s LOVs were hidden by the corded strands of his Egyptian-wrapped hair, and could be seen only when he pulled the tresses back into a ponytail. “Maybe she just fell asleep,” he muttered.

“Not Gabrielle.”

Virgil glanced across the lobby to the half-open door of the conference room, where the droning voice of a presenter could be heard, describing in excruciating detail the numbers obtained in a recent experiment. It was the sixth project review to be laid before the senior staff of Equatorial Systems in a session that had already run three hours. The LOV project was up next, the seventh and last appeal to be laid before a brain-fried audience charged with recommending funding for the coming year.

Gabrielle always did the presenting. The execs loved her. She was a control freak who made you happy to follow along.

“Maybe she lost her farsights,” Virgil suggested without belief.

“She would have called us on a public link. Maybe she found a new boyfriend, got distracted.”

“That’s not it.”

It was Virgil’s private theory that in a world of six and a half billion people, only the hopelessly driven obsessive could out-hustle the masses of the sane—those who insisted on rounded lives, filled out with steady lovers, concerts, vacations, hobbies, pets, and even children. Sane people could not begin to compete with the crazies who lived and breathed their work, who fell asleep long after midnight with their farsights still on, only to waken at dawn and check results before coffee.

Gabrielle had never been one of the sane.

So why hadn’t she called?

Because something had stopped her. Something bad. Maybe a car accident? But if that was it, they should have heard by now.

Virgil’s gaze scanned the field of his own farsights, searching for Gabrielle’s icon, hoping to find it undiscovered on his screen.

Nothing.

Panwar was pacing again, back and forth before the lobby doors. Virgil said, “You’re going to have to do it.”

Panwar whirled on him. “God no. It’s five-thirty on a Sunday afternoon. Half the execs are asleep, and the other half want to get drunk. They emphatically do not want to listen to me.”

“We haven’t got a choice.”

“You could do it,” Panwar said. “You should do it. It’s your fault anyway Nash stuck us in this time slot. If you’d turned in the monthly report when it was due—”

“Remember my career-day talk?”

Panwar winced. “Oh, Christ. I forgot.” Then he added, “You always were a jackass. All right. I’ll give the presentation. But the instant Gabrielle walks through that door, she t

akes over at the podium.”

VIRGIL skulked in the conference-room doorway, as much to make it awkward for anyone to leave early, as to hear what Panwar had to say. The LOV project always confused the new execs, stirring up uncomfortable questions like: What’s it for? Where’s it going? Have any market studies been done?

The project was the problem child in the EquaSys family, refusing to stay on a convenient track to market glory. It was Panwar’s job to make the execs love it anyway.

Or rather, it was Gabrielle’s job. Panwar was only subbing.

“… At the heart of the LOV project are the artificial neurons called asterids. Conceived as a medical device to stabilize patients with an unbalanced brain chemistry …”

Virgil scowled. Wasn’t Panwar’s passion supposed to illuminate his voice, or something? Why had this sounded so much better when they’d rehearsed it with Gabrielle?

“Test animals used in this phase of development began to exhibit enhanced intelligence as measured on behavioral tests, though never for long. The cells tended to reproduce as small tumors of intense activity. Within an average sixty days postimplantation, every test animal died as some vital, brain-regulated function ceased to work.”

Not that Panwar was a bad speaker. He was earnest and quick, and obviously fascinated by his subject, but he wasn’t Gabrielle. The rising murmur of whispered conversations among the execs could not be a good sign.

“The tumor problem was eliminated by making asterid reproduction dependent on two amino acids not normally found in nature. Nopaline is required for normal metabolism, while nopaline with octopine is needed before the asterids can reproduce.”

Virgil shook his head. Nopaline, octopine, what-a-pine? The nomenclature would have been music coming from Gabrielle’s mouth, but from Panwar it was just noise. Virgil glanced wistfully at the lobby door. Still no Gabrielle.

“In the third phase of development, the asterids were completely redesigned once again. No longer did they exist as single cells. Instead, a colony of asterids was housed within a transparent silicate shell, permitting easy optical communication. In effect, EquaSys had created the first artificial life-form, a symbiotic species affectionately known as LOVs—an acronym for Limit of Vision, because in size LOVs are just at the boundary of what the human eye can easily see.”

A new species. To Virgil, the idea still had a magical ring. It was the lure that had drawn him into the project, but to the execs it was old news.

“When implanted on the scalps of test animals, the asterids within each shell formed an artificial nerve, able to reach through a micropore in the skull and past the tough triple layer of the meninges to touch the tissue of the brain. To the surprise of the development team, the LOV implants soon began to communicate with one another, and once again, long-term behavioral effects were observed in test animals. They became smarter, but this time without the development of tumors, or failures in vital functions.”

The momentum of discovery had taken over the project. Virgil had not been part of it then, but he still felt a stir of excitement.

“The original medical application was expanded, for it became apparent that the LOVs might be developed into an artificial or even an auxiliary brain.

“Then came the Van Nuys incident.”

EquaSys had not been involved in that debacle, but the company had been caught in the fallout, when the U.S. government agreed to a two-year moratorium on the development of all artificial life-forms. One of the witnesses in favor had been the original LOV project director. To Summer Goforth, Van Nuys was a wake-up call. She’d publicly renounced her work, and the work of everyone else involved in developing artificial life-forms. Virgil had been brought on board to take Summer Goforth’s place.

“In a compromise settlement EquaSys agreed to abandon animal testing and to export the LOVs to a secure facility aboard the Hammer, the newest platform in low-earth-orbit. From such a venue, the LOVs could not possibly ‘escape into the environment,’ as happened in Van Nuys.”

The LOVs had been so easy to contain. That’s what made them safe.

“Since then our research has been limited to remote manipulation, but that could soon change. The two-year moratorium will expire this June 30. At that time EquaSys will be free to exploit an unparalleled technology that could ultimately touch every aspect of our lives… .”

All that and more, Virgil thought, for if the LOVs could be legally brought Earth-side, then no one need ever know about the LOVs the three of them had smuggled off the orbital during the moratorium period. He still could not quite believe they had done it, and yet … he could not imagine not doing it. Not anymore.

It had been worth the risk. Even if they were found out, it had been worth it. The LOVs were a gift. Virgil could no longer imagine life without them.

The original studies suggested the LOVs could enhance the intelligence of test animals, but Virgil knew from personal experience that in humans the LOVs enhanced emotion. If he wanted to lift his confidence, his LOVs could make it real. If he sought to push his mind into a coolly analytical zone, he need only focus and the LOVs would amplify his mood. Fearlessness, calm, or good cheer, the LOVs could augment each one. But best of all—priceless—were those hours when the LOVs were persuaded to plunge him into a creative fervor, where intuitive, electric thoughts cascaded into being, and time and hunger and deadlines and disappointments no longer mattered. With the LOVs, Virgil could place himself in that space by an act of will.

“All of our research to date,” Panwar said, concluding his historical summary, “has shown without doubt, that LOVs are perfectly safe.”

An icon winked into existence on the screen of Virgil’s farsights—but it was not from Gabrielle. He felt a stir of fear as he recognized the symbol used by EquaSys security. He forced himself to take a calming breath before he whispered, “Link.”

His farsights executed the command and the grim face of the security chief resolved within his screen. Beside it appeared a head-and-shoulder’s image of Dr. Nash Chou, the research director and Virgil’s immediate boss. Nash had hired Virgil to handle the LOV program. Now he turned around in his seat at the head of the conference table, a portly man in a neat business suit, his round face looking puzzled as he gazed back at Virgil.

“Dr. Chou,” the security chief said. “There’s been an incident in Dr. Copeland’s lab.”

A CLEANING robot had found Gabrielle. The little cindy had gone into the project suite just after five, tending to the carpets in the hallway and offices before entering the common room. At five-nineteen it contacted security, reporting that its air-quality sensors had detected the presence of noxious or hazardous airborne vapors.

Security discovered her body at five-thirty-two.

“Oh God no,” someone said. “It can’t be true.”

“Virg?”

That was Panwar. He sounded like a kid again, sixteen years old and scared.

Virgil sat hunched on a sofa in the retreat center’s lobby, his face in his hands. “God, my chest hurts.”

Panwar’s hand closed awkwardly on his shoulder. “Hold on to yourself, Virg. Don’t lose it. We still have to get there. Find out what happened.”

Virgil nodded. They’d driven over together from Honolulu. Significantly, Gabrielle had declined to carpool. She’d been in a hurry Saturday, when Virgil had called. “You two go ahead. I’ve got some business to take care of, so I might be a few minutes late.”

So. Time to head back, then. He started to rise.

“No, wait here,” Panwar said. “I’ll get your car.”

“Get it tomorrow,” Nash Chou interrupted from somewhere nearby. His voice was soothing, fatherly. “It’s getting dark, and neither of you is in any shape to drive.”

So Nash drove them back in the rain. Virgil sat in the shotgun seat, his head bowed against his hand, drowning slowly in a grief that seemed to have nothing to do with feedback from the LOVs. How? he wondered. Why? He was dimly aware of Nash behi

nd the wheel of the Mercedes. The windshield wipers were on. Veils of rain pattered against the glass as the car accelerated into heavy traffic on the freeway.

A light started blinking, somewhere close to Virgil’s eye. Its insistent optical bleating tugged at his consciousness, teased him, forced him to look at it.

It was Panwar’s icon—an infinity sign made to look like a twisted lane of black space containing thousands of stars, set against a powder blue background. Why was it there on the screen of his farsights? Panwar was only a couple feet away, behind him in the backseat.

Still, it was easier to accept the link than to turn around. He tapped a quick code with his fingers, stimulating the microchips embedded in his fingertips to emit faint radio signals, detectable by his farsights.

Panwar’s face replaced the glittery icon. He looked wary, almost defensive as his gaze fixed on Virgil, but he didn’t speak. Instead, typed text in bright white letters appeared in Virgil’s field of view:

→ Don’t say a word! Understand me? Don’t let Nash know we’re talking.

Virgil stared at the message, trying to make sense of it, until a new couplet replaced the original sentences:

→ Virg? You understand?

Without looking up or lowering the hand that shaded his farsights, Virgil dipped his head in a slight nod. More words arrived:

→ Pull yourself together, man, because you are scaring the shit out of me!!!

Virgil started to open his mouth.

→ No! Don’t talk!!! Listen to me, and try to remember what’s at stake. Gabrielle’s dead. I can’t believe it either, but we can’t bring her back. We’re not that far along yet.

Virgil squeezed his eyes shut, wondering if they ever would have the power to heal death. The human body was a machine; he knew that. He had looked deep into its workings, all the way down to the level of cellular mechanics, and there was no other way to interpret the processes there than as the workings of an intricate, beautiful, and delicate machine.

Machines, though, could be repaired. They could be rebuilt, copied, and improved—and sometimes it seemed inevitable that all of that would soon be possible for the human machine too.

Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories

Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories Pacific Storm

Pacific Storm Edges

Edges The Red

The Red The Red: First Light

The Red: First Light The Martian Obelisk

The Martian Obelisk Limit of Vision

Limit of Vision Going Dark

Going Dark The Last Good Man

The Last Good Man The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2)

The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2) Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2)

Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2) The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013 The Dread Hammer

The Dread Hammer Skye Object 3270a

Skye Object 3270a The Bohr Maker

The Bohr Maker