Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories

Nightside on Callisto and Other Stories Pacific Storm

Pacific Storm Edges

Edges The Red

The Red The Red: First Light

The Red: First Light The Martian Obelisk

The Martian Obelisk Limit of Vision

Limit of Vision Going Dark

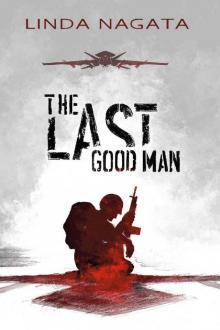

Going Dark The Last Good Man

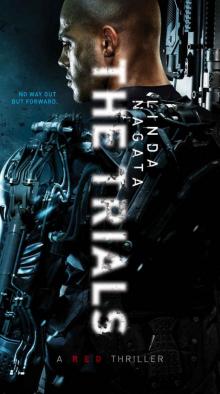

The Last Good Man The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2)

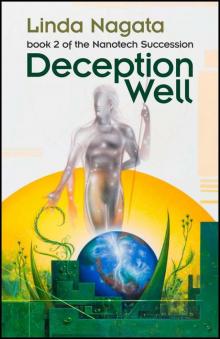

The Trials (The Red Trilogy Book 2) Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2)

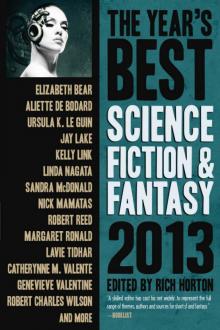

Deception Well (The Nanotech Succession Book 2) The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013

The Year's Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2013 The Dread Hammer

The Dread Hammer Skye Object 3270a

Skye Object 3270a The Bohr Maker

The Bohr Maker